To smutne, że ‘odkrylam’ wielkiego artyste Ricardo Pérez Alcalá tuz po jego śmierci. Ale mimo, iz już go nie ma wsrod nas, jego sztuka pozostanie z nami na zawsze.

Kariera artystyczna Ricardo Perez Alcala jest naprawdę imponująca. W swoim życiu, zdobył on wiele nagród zarówno w Boliwii, jak i za granicą. Studiował na Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Potosi i po raz pierwszy wystawił swoje prace w wieku piętnastu lat, kiedy udało mu się sprzedać około trzydziestu obrazow. Później ukończyl jeszcze architekture na Universidad Mayor de San Andrés w La Paz (1963), ale swoje życie zawodowe poświęcił malarstwu.

Po wygraniu wszystkich głównych nagrod w dziedzinie malarstwa i rysunku w Boliwii, podrozowal po całej Ameryce Łacińskiej, a jego tworczosc zostala szczególnie doceniona w Meksyku, gdzie mieszkał przez 14 lat, i gdzie czterokrotnie zdobył Nagrodę Państwową w dziedzinie akwareli. Sztuka Ricardo Perez Alcala została również uznana przez jury World Grand Prix akwareli oraz przez Francuskie MInisterstwo Kultury i Sztuki. Ostatnio zas został zaproszony do wystawienia swoich prac w Luwrze w Paryżu, co jest bezprecedensowym wydarzeniem dla Boliwijskiego artysty.

“Mistrz niemożliwych kolorow” zmarł w domu, zaprojektowany przez siebie. Ta ekstrawagancka rezydencja, podobna jest do domu-muzeum Salvadora Dali w Portlligat, ale posiada wlasny styl baroku- meztizo. Dom znajduje się w południowej czesci miasta La Paz i posiada 3 studia. Jedno z nich zanjduje sie obok sypialni artysty, gdzie malował przed snem. Jest tam takze mała kuchnia, gdzie przygotowywal na predce coś do jedzenia, aby moc szybko wrocic do tworzenia.

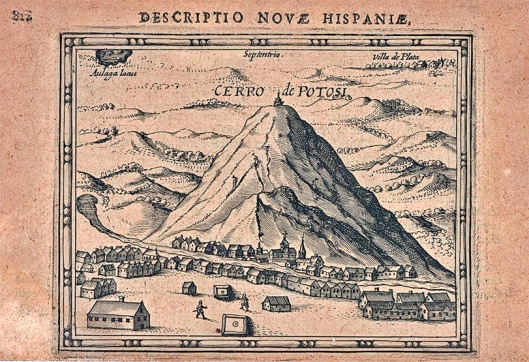

Urodzony w 1939 roku w Potosi – miescie o wielkiej historii, Pérez Alcalá był wielbicielem Diego Velazqueza, Rembrandta i Leonardo da Vinci. Często mowil takze o obrazach hiszpańskiego artysty Antonio Lópeza, szczegolna estema darzyl natomias współczesna akwarele amerykańskiego malarza Andrew Newell Wyeth’a.

Analizując jego akwarele mozna powiedziec ironicznie, że artysta był “antyakwarelista”, ponieważ pracował on poza kanonem tradycyjnej angielskiej akwareli, który głosi, że wykonanie obrazu w tej technice nie powinno zająć więcej niż dwie godziny, ponieważ po tym czasie nie jest już akwarela. Ricardo, uwazal, ze przypomina to wykonanie nudnego i prostego szkicu. Wypracował wiec swój własny sposób malowania i czasem, wykonczenie akwareli w najdrobniejszych szczegółach zajmowalo mu kilka miesiecy .

Pérez Alcalá po mistrzowsku oddawal światło, ktore w polaczeniu z elegancka paleta barw ‘tchnelo’ w jego akwarele codziennego życia, atmosferę tajemnicy i niepokoju.

Ale malarz nie ograniczal się tylko do martwych natur i pejzaży, wręcz przeciwnie, zawsze był innowacyjnym twórcą z wyobraźnią. Podczas swojej kariery, malowal wielkie osobowości z Meksyku i Boliwii, jak rowniez setki autoportretów w różnych technikach. W ciagu 60 lat stworzyl ponad 6000 obrazów, odzwierciedlajacych jego ogromną etykę pracy.

Ricardo Perez Alcala zmaterializował wcześniej niewyobrażalne wyzwania: w ciągłym poszukiwaniu nowych form wyrazu, wypracowal wlasna technike “akwareli na desce” – malowanie na otenkowanej drewnianej powierzchni, pozwala na mniejsza absorcje akwareli niz na papierze, dając większą intensywnosc i jasność kolorów.

Ponadto, był znanym architektem, rzeźbiarzem, karykaturysta oraz utalentowanym kucharzem-samoukiem i wspaniałym gospodarzem. Byl rowniez specjalista w zakresie kolekcjonerstwa oraz nauczycielem i mentorem kilku bardzo znanych artystów, miedzy innymi akwarelisty Dario Antezana z Cochabamby (syna jego najlepszego przyjaciela Gíldaro Antezana). Jako pedagog w Szkole Sztuk Pięknych w El Alto nauczal dwie artystki młodego pokolenia: Monica Rina Mamani i Rosmery Mamani Ventura, które wziely sobie jego lekcje do serca, osiagajac zawodowy sukces .

Wierzył, iz tylko poprzez ciezka prace da sie osiagnac doskonalosc: ‘El que escucha olvida, el que mira recuerda pero el que hace aprende”.

Kto słucha zapomina, kto patrzy pamięta, a kto probuje uczy sie.

Co ciekawe, w swojej tworczosci zawsze zawieral refleksje nad śmiercią. Jego prace sa zwykle związane z magicznym realizmem, hiperrealizmem i surrealizmem, ale z biegiem lat stały się bardziej tajemnicze i melancholijne. Powiedział kiedyś: “Me interesa el arte sólo cuando hay misterio”.

“Jestem zainteresowany tylko taka sztuka, która zawiera tajemnicę”.

Może dlatego tez, namalował swój autoportret w przepięknej akwareli na desce, ktora sam nazwal “Reclinado sobre mi Tumba” (“Leżący na swoim grobie“) (1992). To arcydzieło jest rodzajem malarskiego testamentu, w ktorym malarz zportretowal siebie jako zmartwychwstałego i nieśmiertelnego – tylko artysta jego wielkosci moze zapisac sie w pamięci zbiorowej oraz wszystkich tych, którzy cenia dobrą sztukę.

![1004519_10151788473419476_991506052_n[1]](https://i0.wp.com/boliviainmyeyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/1004519_10151788473419476_991506052_n1.jpg?resize=620%2C628&ssl=1)

Ten autoportret mówi takze wiele o szlachetności Ricardo Pérez Alcalá, ponieważ zawarl on w obrazie szkielet koguta, przypominający o Gíldaro Antezana, ‘bracie’ i przyjacielu, który tak jak on wiernie uprawial zawod malarza i walke kogutów. Wreszcie, na szczycie kamienia można zobaczyć małe drzwi prowadzące do nieznanego wymiaru, z wieloma akwarelami rozplywajacych sie w czasie. “Leżący na swoim grobie” jest kameralnym, zabawnym, proroczym, tajemniczym, symbolicznym i reprezentatywnym dziełem sztuki, które podsumowuje dorobek i zycie artysty. Powiedział on kiedyś: ‘Lo único que le pido la vida es morirme con el último brochazo”.

Jedyne czego chcę od życia to umrzeć z ostatnim pociagnieciem pedzla

Ricardo Pérez Alcalá spełnil to marzenie, dla którego poswiecil całe swoje życie: żyl i umarl jako artysta. Teraz, zostawia nam w spadku swa cenną pracę, czym potwierdza, że prawdziwi artyści nigdy nie umierają.

Wniose cos do ludzkości, powiedziałem, i stałem się malarzem.

Voy aportar algo la humanidad, dije, y mnie converti en pintor.

Ricardo Perez Alcala

Fragmenty wybrane i przetlumaczone z oryginalnego tekstu dr. Harolda Suárez Llápiz, ucznia, przyjaciela artysty i wielbiciela jego sztuki. Lekarza, badacza i krytyka sztuki wspolczesnej. Administratora ‘Arte Boliviano Contemporáneo “.

***

‘You can live without the art, but you can’t BE without the art’

“Se puede vivir sin el arte pero no se puede ser sin el arte”

Ricardo Pérez Alcalá (1939-2013)

![9[1]](https://i0.wp.com/boliviainmyeyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/91.jpg?resize=587%2C440&ssl=1)

It’s sad that I discovered the great artist Ricardo Pérez Alcalá so late, after his death. But although he is gone, his art will stay with us forever.

The artistic career of Ricardo Perez Alcala is truly impressive. In his lifetime, he had won many awards both in Bolivia as abroad. He studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Potosi and held his first exhibition at fifteen, when he managed to sell around thirty paintings. He later graduated as an architect at the Universidad Mayor de San Andrés in La Paz (1963) but devoted his professional life to painting.

After winning all the major awards in painting and drawing in Bolivia, he had traveled throughout Latin America and his work was particularly recognized in Mexico, where he had lived for 14 years and where he won the National Watercolor Prize on four occasions. Ricardo Perez Alcala was also recognized at Watercolor World Grand Prix and by the National Federation of French Culture and European Arts . Recently he was invited to exhibit his work at the Louvre in Paris, an unprecedented event for a Bolivian artist.

‘The master of impossible colors’ died in the house that he designed himself. This extravagant residence is similar to the house-museum of Salvador Dali in Portlligat, but with a very own meztizo – baroque style. In this vast refuge located in the Southern Zone of the city of La Paz, he had 3 studios. Moreover, he built a workshop right next to his bedroom, where he painted before going to sleep. There is also a small kitchen, where he prepared quickly something to eat, so he wouldn’t interupt his artistic creation.

Born in 1939 in Potosi – the city of a great history and art, Pérez Alcalá was an admirer of Diego Velazquez, Rembrandt and Leonardo Da Vinci. He also spoke often about the pictorial quality of Spanish artist Antonio López. But above all, the Bolivian painter had a great admiration for a contemporary watercolor by American painter Andrew Newell Wyeth.

Analyzing his watercolors one would say ironically that Perez Alcala was an “antiacuarelista”, because he was working outside the canons of traditional English watercolor, proclaiming that this technique should not take more than two hours in execution, since after this time is no longer watercolor. For the artist, this ‘old school’ was like a boring resembling of a simple sketch. He developed his own way of painting and it took him up to several months, to finish the watercolour in minute detail, punishing the paper with endless color glazes to apply this extra element that makes the difference: a large dose of creativity. Pérez Alcalá masterfully handled the light – which together with elegant palete of colours, printed in his watercolors mysterious and disturbing atmosphere of everyday life.

But Ricardo Perez Alcala was not limited to the usual still lifes and landscapes, on the contrary, he was always a creator with innovating imagination. During his career, he has portrayed several personalities from Mexico and Bolivia. He also painted a hundred self-portraits in various styles. More than 6,000 paintings in more than 60 years as a painter reflect his tremendous work ethic.

Ricardo Perez Alcala has materialized previously unimaginable challenges: in his constant search for new forms of expression he developed his own technique of “watercolor on board” – a preparation of plaster on a wooden surface, which allows for less absorption of the watercolor that it does on paper, giving the color more brightness and intensity.

He also was a renowned architect, sculptor, caricaturista, talented and accomplished self-taught chef and great host, specialist in art collecting. He was a teacher and mentor of several very prominent artists, including watercolorist Dario Antezana from Cochabamba (son of his best friend Gíldaro Antezana). As an educator at the School of Fine Arts in El Alto, he taught two artists of the new generation: Monica Rina Mamani and Rosmery Mamani Ventura, who knew how to make the most of his lessons.

He believed in a hard work in order to reach an exelence, saying: “El que escucha olvida, el que mira recuerda pero el que hace aprende”.

Who listens forgets, who looks remembers, but who does learns.

It is interesting, that he always made a reflection on death. His work is usually associated with magical realism, hyperrealism and surrealism, but with the passing of the years it became more cryptic, melancholyc. He said once: ‘Me interesa el arte sólo cuando hay misterio”.

‘I am interested only in art that has a mystery’.

Maybe that’s why he painted his self-portrait in a stunning watercolor on board, that he himself called “Reclinado sobre mi tumba” (“Reclining on my grave“) (1992). This masterpiece may be a sort of pictorial testament. The great painter paints himself as resurrected, immortal, as only an artist of his level may be recorded in the collective memory of society and those who appreciate good art.

This self-portrait also says much about the nobility of Ricardo Pérez Alcalá, since the image shows the skeleton of a rooster, reminiscent of Gíldaro Antezana, the ‘brother’ and friend, that like himself, faithfully exercised the trade of a painter and cockfighting.

![267351_10151793915354476_1216245529_n[1]](https://i0.wp.com/boliviainmyeyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/267351_10151793915354476_1216245529_n1.jpg?resize=620%2C465&ssl=1) Fot. Harold Suárez Llápiz

Fot. Harold Suárez Llápiz

Finaly, on top of the stone you can see a small door leading into an unknown dimension, and many watercolor papers floating and dispersing in time. “Reclining on my grave” is an intimate, playful, prophetic, cryptic, symbolic and representative piece of art that sums up his work. He once said: ” Lo único que le pido a la vida es morirme con el último brochazo”.

‘The only thing I want from life is to die with the last brushstroke.’

Ricardo Pérez Alcalá fulfilled the dream for which he fought all his life: to live and die as an artist. Now, he leaves us a legacy of his valuable work – it’s true that great artists never die.

I will contribute something to humanity, I said, and I became a painter.

“Voy a aportar algo a la humanidad, dije, y me convertí en pintor”

Ricardo Perez Alcala

Fragments choosen from the original text of Dr. Harold Suárez Llápiz – student, friend and admirer of Ricardo Pérez Alcalá’s art. Doctor MD, researcher and art critic. Administrator of ‘Arte Boliviano Contemporáneo’.

![51927_447228654475_243304844475_5012979_1894248_o[1]](https://i0.wp.com/boliviainmyeyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/51927_447228654475_243304844475_5012979_1894248_o1.jpg?resize=620%2C435&ssl=1)

![800px-Marraqueta_paceña[1]](https://i0.wp.com/boliviainmyeyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/800px-marraqueta_pacec3b1a1.jpg?resize=620%2C440&ssl=1)

![69142_10151212139389476_2004546010_n[1]](https://i0.wp.com/boliviainmyeyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/69142_10151212139389476_2004546010_n1.jpg?resize=620%2C454&ssl=1)

![1004519_10151788473419476_991506052_n[1]](https://i0.wp.com/boliviainmyeyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/1004519_10151788473419476_991506052_n1.jpg?resize=620%2C628&ssl=1)

![9[1]](https://i0.wp.com/boliviainmyeyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/91.jpg?resize=587%2C440&ssl=1)

![267351_10151793915354476_1216245529_n[1]](https://i0.wp.com/boliviainmyeyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/267351_10151793915354476_1216245529_n1.jpg?resize=620%2C465&ssl=1) Fot. Harold Suárez Llápiz

Fot. Harold Suárez Llápiz ![51927_447228654475_243304844475_5012979_1894248_o[1]](https://i0.wp.com/boliviainmyeyes.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/51927_447228654475_243304844475_5012979_1894248_o1.jpg?resize=620%2C435&ssl=1)